Introduction

Building on the work we did in the previous post, I spent today building a normal SABR volatility surface for BTC options, with the end-goal of pricing inverse options on Deribit (which will be in the next post). This post is about what actually mattered, what broke repeatedly, and what finally made the model behave. This is not a SABR tutorial. It is about scaling, units, and why crypto makes you pay attention to things that rate quants get for free!

My Choice of Model

Bitcoin options are quoted in implied volatility, but the underlying is a large positive price level, not a rate or a yield. Let’s set some notation:

be the BTC spot price at time

be the forward price of BTC for maturity

be the option strike

be time to expiry in years

Working in Black lognormal volatility assumes dynamics proportional to , which creates unstable wing behaviour for large underlying levels (despite it scaling with the price level). This is because for a given log-moneyness

, the absolute strike distance satisfies:

; and so when

is large, the same log-moneyness corresponds to very large absolute price differences. This amplifies:

- convexity effects

- sensitivity to extrapolation

- numerical instability in the wings

This is especially relevant for BTC, where .

A normal (Bachelier) volatility, quoted in USD per , is a much more natural object for BTC when the goal is stability and smooth extrapolation.

This motivates using normal SABR, with the elasticity parameter fixed to zero: .

Vol-of-Vol Is Tiny

In normal SABR with , the smile curvature enters through the variable

, defined as:

where:

is the SABR volatility level parameter, with units USD per

is the volatility of volatility parameter

is the forward price

is the strike

For BTC we have these sorts of numbers:

- In the wings,

or more

- Therefore

is on the order of

Which means if one naively sets (as I did):

then becomes enormous, and the SABR approximation explodes. Model vols jump into the millions, the Excel Solver becomes unstable, and the calibration fails.

For BTC in USD price units, must be on the order of

. So, once

is constrained to this scale, the model immediately stabilises.

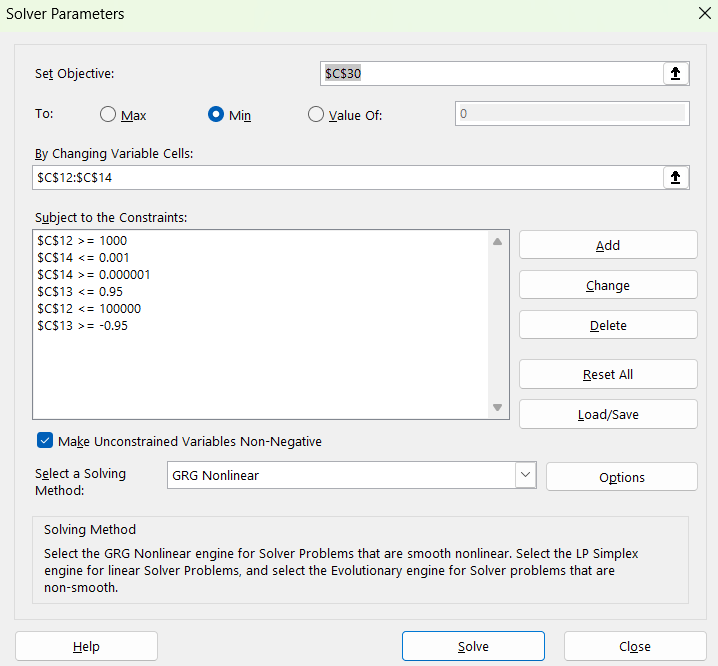

This was the single most important fix. So my Solver Parameters were set like this. For a particular time to expiry, in cell C12 was alpha (which had to be strictly greater than 1000 so that it didn’t find the local minimum created at , and another one up at

), in cell C13 was rho (which had the usual constraint of

), and in cell C14 was the vol-of-vol (which I had to really strictly constrain, otherwise this kept exploding!),

Why Relative SSE was Essential?

Market normal vols for BTC are on the order of to

. Using an absolute squared error objective,

produces objective values in the billions, which is numerically bad to optimisers like the Excel Solver.

Instead, the calibration objective was defined as a relative squared error:

where:

indexes strikes or moneyness points

are user-chosen weights

are market normal vols

are model normal vols

This produces a dimensionless objective of order , which makes optimisation well behaved across maturities and strikes.

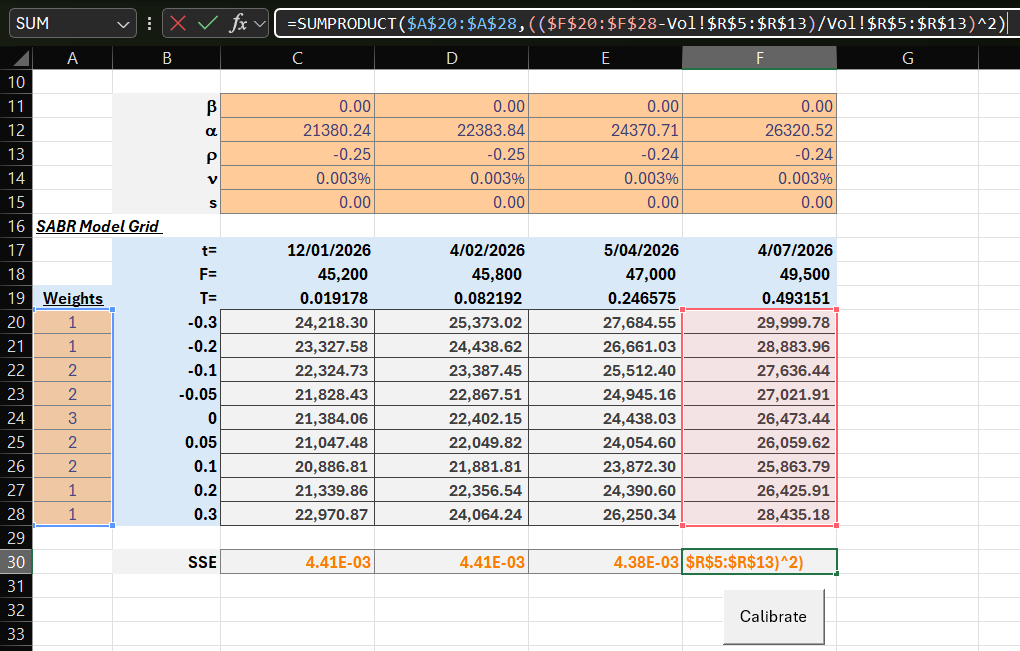

So you can see here in my SSE formula, I use the relative SSE variant, where I have divided by the market quotes (in cells Vol!$R$5:$R$13):

The Role of Weights

When calibrating a parametric volatility surface, the objective function is not uniquely defined. The choice of weights determines which parts of the smile the model is incentivised to fit accurately, and which parts it is allowed to smooth over.

In this calibration, the objective function takes the form:

- where

indexes moneyness points for a fixed expiry,

is the market normal volatility at point

,

is the model normal volatility at the same point,

is a non-negative weight applied to that point.

The weights were chosen by me. They are not implied by the model.

Since BTC volatility smiles are quite noisy in the wings, and often quoted with lower liquidity far from ATM, the smile is highly sensitive to small data errors when working in price units.

If all points are given equal weight, the Solver will often overfit noisy wing points, distort curvature to reduce a few large absolute errors, and sacrifice ATM stability to chase illiquid strikes.

This is especially problematic when the vols are large ( USD), and curvature is controlled by a very small parameter

The weights are applied as a simple function of moneyness, and the exact numbers are not special. What matters more is the ordering, which simply reflects three facts:

- ATM options are the most liquid

- ATM vols dominate pricing and hedging

- Wing quotes contain more noise and less information

The Role of the Shift Parameter

When working with log-moneyness, the expression

implicitly assumes:

- stable behaviour as

While BTC prices are strictly positive, inverse options and payoff transformations naturally involve expressions in , which introduce numerical and structural instability near low strikes.

To address this, a shift parameter is introduced.

Shifted Log-Moneyness

We define the shifted forward and shifted strike to be:

where:

is a shift parameter, expressed in USD

The shifted log-moneyness is then defined as:

This replaces as the coordinate used to index the smile.

Note that:

- when

, this reduces to standard log-moneyness

- when

, low strikes are pushed away from zero

- the mapping between

and

is smooth and invertible

How the Shift Enters the SABR Calibration

The SABR model itself does not change, all parameters remain the same. Instead, it is how the strikes are generated and interpreted. When we are given now log-moneyness , a forward BTC price in USD

, and a shift

, then the strike used in the SABR formula becomes:

which makes the smile parameterised in shifted log-moneyness and the model should still behave nicely in the wings. But most importantly, the calibration model should be compatible with inverse-payoff transformations (next blog).

Note that the shift parameter is a global parameter and is not calibrated, and only candidate values of the shift amount will be tested.

Calibration Results

For now, just to get the calibration working, we will use a null shift parameter.

Here are the results:

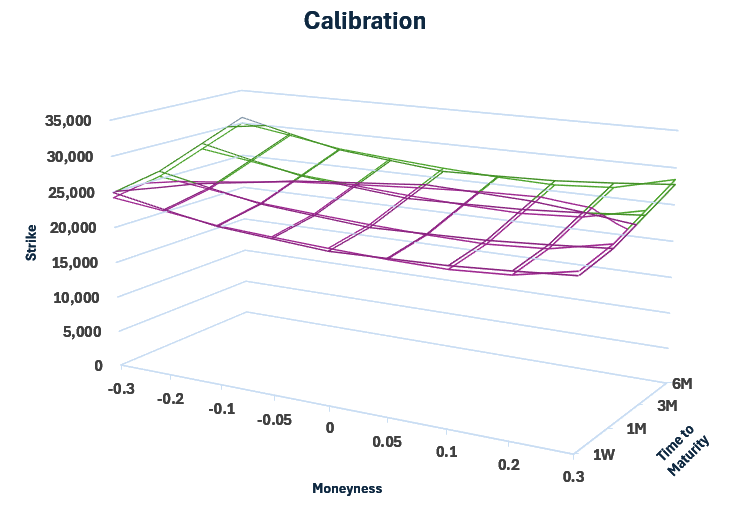

The surface plot above shows the calibrated normal SABR volatility surface alongside the corresponding market-quoted normal volatilities, using a null shift parameter. The model reproduces the observed term structure and smile shape across all quoted maturities, with particularly close agreement around the ATM region where liquidity is highest. Deviations between the model and market surfaces are small relative to the overall volatility level and exhibit no systematic structure, indicating that the calibration is capturing the dominant features of the smile rather than overfitting local noise.

Importantly, the fitted parameters vary smoothly across maturities, and the resulting surface is well behaved in both moneyness and time. This confirms that normal SABR with provides a stable and parsimonious representation of the BTC volatility surface in absolute price space. The remaining discrepancies are consistent with market microstructure effects and discrete quoting rather than model misspecification, making the calibrated surface suitable for interpolation, extrapolation, and downstream pricing applications.

Shifted-SABR

Normal SABR does not require a shift for mathematical validity. The model already accommodates negative values cleanly.

A shift becomes relevant only when:

- working in log-moneyness

- transitioning to Black-style implied volatilities

- building a unified framework compatible with inverse or lognormal conventions

At this stage, the shift is set to .

Why inverse BTC options change the problem

The ultimate goal is to price inverse BTC options on Deribit. These options:

- Settle in BTC

- Have payoffs that are non-linear in the BTC price

- Cannot be priced correctly by plugging a normal or Black vol into a standard USD-settled formula

This means the next step is not modifying SABR further, but rather building a pricing layer that respects:

- the inverse payoff

- the underlying variable transformation

- Deribit’s implied volatility convention

Only once prices are correct does it make sense to introduce shifted moneyness or shifted SABR.

Conclusion

What I discovered in this exercise is that SABR itself is not fragile, the units are!

Once the scale is correct, normal SABR works extremely well for BTC. Most issues arise from importing intuition from rates or equities without adjusting for the fact that the underlying is a fifty-thousand-dollar asset, not a five-percent yield.

With a stable normal SABR surface calibrated to a synthetic market grid, the next step is to replace that grid with real Deribit market quotes, and to extend the framework to include a shift parameter in a controlled way.

This section outlines how those two steps will be done.

Appendix

The SABR calibration is automated using a small VBA layer that wraps Excel’s Solver and applies it consistently across maturities. For each expiry, the code constructs a relative least-squares objective based on weighted differences between model and market normal volatilities, and then minimises this objective by adjusting the SABR parameters ,

, and

, while holding

and the shift parameter fixed. Tight bounds are imposed on all parameters, particularly on

, to ensure numerical stability in USD price units. The calibration proceeds from the longest maturity to the shortest, seeding each expiry with the fitted parameters from the previous maturity to improve convergence and enforce smoothness in the term structure. This automation removes manual intervention from the calibration process, ensures reproducibility, and allows the volatility surface to be recalibrated quickly as market data updates.

Option Explicit

'===========================================================

' Shifted SABR Normal (Bachelier) implied vol approximation.

'

' Written by: Benjamin Whiteside

' Last Modified: 06/01/2026

'

' Hagan-style normal SABR on shifted F,K:

' Ft = F + shift, Kt = K + shift

'

' Returns normal vol in same price units as F,K (e.g. USD / sqrt(year)).

'

' Signature:

' SABR_N_Shift(F, K, T, alpha, beta, rho, nu, shift)

'

' Notes:

' - Uses ATM expansion when |Ft-Kt| is tiny to avoid 0/0.

' - Assumes T in years (ACT/365 or your chosen convention).

' - Requires alpha>0, nu>=0, |rho|<1.

'===========================================================

Public Function SABR_N_Shift( _

ByVal F As Double, _

ByVal K As Double, _

ByVal T As Double, _

ByVal alpha As Double, _

ByVal beta As Double, _

ByVal rho As Double, _

ByVal nu As Double, _

ByVal shift As Double) As Double

On Error GoTo FailFast

' --- Basic guards

If T <= 0# Then

SABR_N_Shift = 0#

Exit Function

End If

If alpha <= 0# Then

SABR_N_Shift = CVErr(xlErrNum)

Exit Function

End If

If nu < 0# Then

SABR_N_Shift = CVErr(xlErrNum)

Exit Function

End If

If rho <= -0.999999 Or rho >= 0.999999 Then

SABR_N_Shift = CVErr(xlErrNum)

Exit Function

End If

If beta < 0# Or beta > 1# Then

SABR_N_Shift = CVErr(xlErrNum)

Exit Function

End If

Dim Ft As Double, Kt As Double, d As Double

Ft = F + shift

Kt = K + shift

d = Ft - Kt

' If beta>0 we will use powers of Ft, Kt, so they must be positive

If beta > 0# Then

If Ft <= 0# Or Kt <= 0# Then

SABR_N_Shift = CVErr(xlErrNum)

Exit Function

End If

End If

' ATM threshold: relative to scale of prices

Dim atmTol As Double

atmTol = 0.0000001 * (1# + Abs(Ft) + Abs(Kt))

' ---------- ATM branch ----------

If Abs(d) < atmTol Then

SABR_N_Shift = SABR_N_ATM(Ft, T, alpha, beta, rho, nu)

Exit Function

End If

' ---------- Non-ATM branch ----------

Dim FK As Double, A As Double

FK = Ft * Kt

' For beta not 0, FK must be positive (powers). With shift it should be.

If beta <> 0# Then

If FK <= 0# Then

SABR_N_Shift = CVErr(xlErrNum)

Exit Function

End If

End If

A = PowSafe(FK, (1# - beta) / 2#)

Dim z As Double, xz As Double

z = (nu / alpha) * A * d

xz = XofZ(z, rho)

' Strike correction B

Dim oneMinusB As Double

oneMinusB = 1# - beta

Dim Bcorr As Double

Bcorr = 1# _

+ (oneMinusB * oneMinusB / 24#) * (d * d / PowSafe(FK, 1# - beta)) _

+ (oneMinusB ^ 4 / 1920#) * (d ^ 4 / PowSafe(FK, 2# - 2# * beta))

' Time correction C

Dim Ccorr As Double

Ccorr = ( _

(oneMinusB * oneMinusB / 24#) * (alpha * alpha / PowSafe(FK, 1# - beta)) _

+ (rho * beta * nu * alpha / (4# * PowSafe(FK, (1# - beta) / 2#))) _

+ ((2# - 3# * rho * rho) / 24#) * (nu * nu) _

) * T

' Main normal vol formula:

' sigmaN = alpha*(FK)^(beta/2) / Bcorr * (z/x(z)) * (1 + Ccorr)

Dim pre As Double, ratio As Double

pre = alpha * PowSafe(FK, beta / 2#) / Bcorr

' z/xz tends to 1 as z->0, but we're not ATM here; still, be safe:

If Abs(xz) < 1E-16 Then

ratio = 1#

Else

ratio = z / xz

End If

SABR_N_Shift = pre * ratio * (1# + Ccorr)

Exit Function

FailFast:

SABR_N_Shift = CVErr(xlErrValue)

End Function

'===========================================================

' ATM normal-vol expansion (shifted already applied, input is Ft)

' sigma_ATM = alpha * Ft^beta * (1 + [ ... ] * T)

'===========================================================

Private Function SABR_N_ATM( _

ByVal Ft As Double, _

ByVal T As Double, _

ByVal alpha As Double, _

ByVal beta As Double, _

ByVal rho As Double, _

ByVal nu As Double) As Double

Dim oneMinusB As Double

oneMinusB = 1# - beta

' Handle beta=0 cleanly: Ft^beta = 1

Dim FtPowBeta As Double

FtPowBeta = PowSafe(Ft, beta)

Dim term As Double

term = ( _

(oneMinusB * oneMinusB / 24#) * (alpha * alpha / PowSafe(Ft, 2# - 2# * beta)) _

+ (rho * beta * nu * alpha / (4# * PowSafe(Ft, 1# - beta))) _

+ ((2# - 3# * rho * rho) / 24#) * (nu * nu) _

) * T

SABR_N_ATM = alpha * FtPowBeta * (1# + term)

End Function

'===========================================================

' x(z) helper for SABR (Hagan)

' x(z) = ln( (sqrt(1 - 2*rho*z + z^2) + z - rho) / (1 - rho) )

' For small z, use series x(z) ~ z to avoid precision loss.

'===========================================================

Private Function XofZ(ByVal z As Double, ByVal rho As Double) As Double

Dim absz As Double

absz = Abs(z)

If absz < 0.00000001 Then

' For tiny z, x(z) ~ z (sufficient; prevents 0/0 noise)

XofZ = z

Exit Function

End If

Dim inside As Double, num As Double, den As Double

inside = 1# - 2# * rho * z + z * z

If inside < 0# Then

' Numeric guard (shouldn't happen for real params)

inside = 0#

End If

num = Sqr(inside) + z - rho

den = 1# - rho

If num <= 0# Or den <= 0# Then

' Fallback: if expression is numerically bad, approximate with z

XofZ = z

Else

XofZ = Log(num / den)

End If

End Function

'===========================================================

' Safe power: handles x^p for x>0, and x=0 for p>0

' For negative x and non-integer p, returns error by raising.

'===========================================================

Private Function PowSafe(ByVal x As Double, ByVal p As Double) As Double

If x = 0# Then

If p > 0# Then

PowSafe = 0#

Exit Function

Else

Err.Raise vbObjectError + 513, , "PowSafe: 0 to non-positive power"

End If

End If

If x < 0# Then

' Only allow integer powers for negative base

If Abs(p - CLng(p)) > 0.000000000001 Then

Err.Raise vbObjectError + 514, , "PowSafe: negative base with non-integer power"

End If

End If

PowSafe = x ^ p

End Function

Final Implementation Notes in VBA & Numerical Considerations

The SABR implementation applies the shift at the level of the forward and strike, defining and

. This is a genuine change of coordinates rather than a post-processing adjustment to the volatility, and it ensures the model remains well behaved when working in log-moneyness or when transitioning to inverse or lognormal pricing conventions. All inputs are expressed in absolute price units, with

,

, and

in USD, time

in years, and the output normal volatility

returned in USD per

. In this setting, the SABR parameter

directly controls the ATM normal volatility when

, while the volatility-of-volatility parameter

must be numerically small for large-price underlyings such as BTC, typically on the order of

to

.

The code confirms numerical stability by separating the ATM and non-ATM regimes. When the shifted forward and strike are close, the implementation switches to the analytic ATM expansion to avoid the limit in the

term of the Hagan approximation. Away from ATM, the full asymptotic formula is used, including the standard strike-dependent and time-dependent correction terms. Additional guards enforce parameter validity and return Excel errors for invalid configurations, ensuring that the calibration process remains robust when driven by Solver. Together, these design choices prioritise stability and interpretability over unnecessary generality, which is essential when calibrating normal SABR in absolute price space.